Bundjalung origin story - the Three Brothers

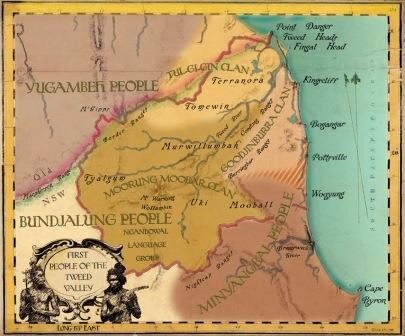

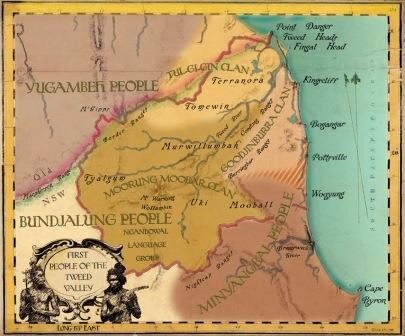

Long ago, Berrung, with his two brothers, Mommóm and Yaburóng, came to this land. They came with their wives and children in a great canoe, from an island across the sea. As they came near the shore, a woman on the land made a song that raised a storm which broke the canoe in pieces, but all the occupants, after battling with the waves, managed to swim ashore. This is how 'the men', the baigal black race, came to this land. The pieces of the canoe are to be seen to this day. If anyone will throw a stone and strike a piece of the canoe, a storm will arise, and the voices of Berrung and his boys will be heard calling to one another, amidst the roaring elements. The pieces of the canoe are certain rocks in the sea. At Ballina, Berrung looked around and said nyung? and all the baigal about there say nyung to the present day, that is they speak the Nyung dialect. Going north to the Brunswick, he said minyung, and the Brunswick River paigal say minyung to the present day. On the Tweed he said ngando to the present day. this is how the blacks came to have different dialects. Berrung and his brothers came back to the Brunswick River where he made a fire, and showed the paigal how to make fire. He taught them their law about the kippara, and about marriage and food. After a time, a quarrel arose, and the brothers fought and separated, Mommóm going south, Yaburóng west, and Berrung keeping along the coast. This is how the paigal were separated into tribes.

Recorded by Livingstone 1892

Transcribed by Margaret Sharpe 2023

Published in Gurgun Mibiñyah and used with permission from author.